Have you ever made an important decision for your organization - one with high stakes or a costly outcome - and wondered, “Did I make the best possible choice?” If you have, how did you answer that question? Most people would say you cannot answer the question until you’ve observed the results: they think it was a good decision because it turned out well.

Decision quality describes the process of coming to a high-quality decision that is backed by research and decades of practice. Fundamental to decision quality is the concept that decisions should not, and can not, be judged by their outcome. An outcome may stretch out for many years, which would require you to withhold judgment until everything there is to know about the result is available. That’s not practical. Nor is it useful to decision makers, who must be able to judge the quality of a decision at the time they are making it.

During this moment of truth, decision makers must be able to say, “We have done everything we can to assure that we are making the best possible decision.”

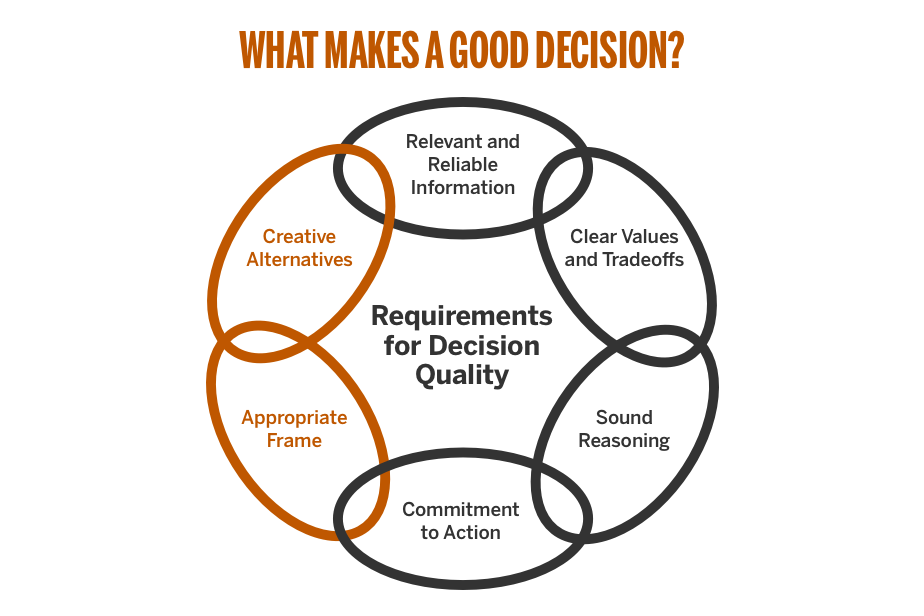

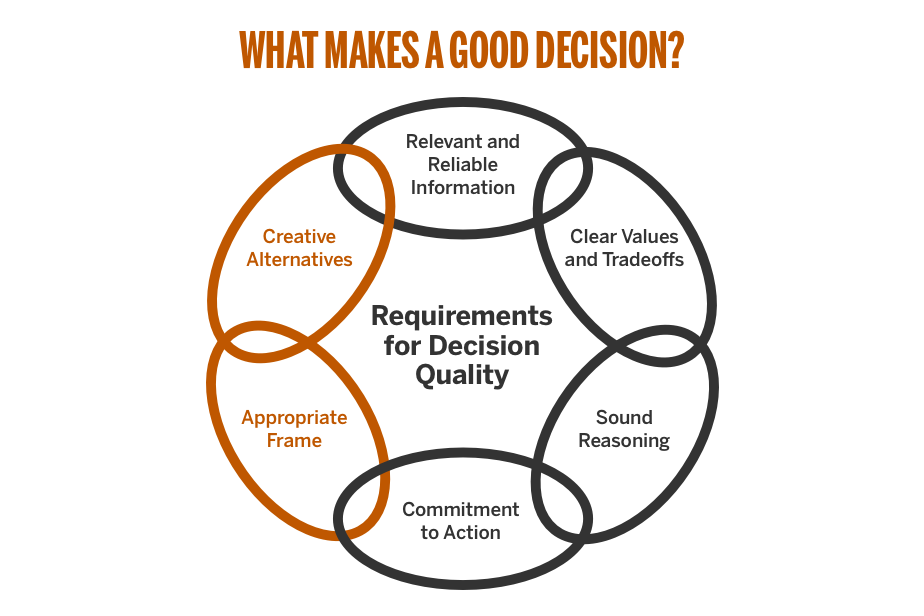

What Makes a Good Decision?

The quality of a decision is not determined by its outcome. This is especially true when the decision involves strategic questions and significant risks. Instead, it’s determined by what went into making it. But, how do you determine what a good decision is? Strategic decision making is a discipline and focused area of study that includes the following elements:

- Correct framing of a problem or opportunity

- Realistic and feasible alternatives

- Relevant and reliable information to guide the ultimate choice

- Clear values and trade offs

- Sound reasoning in the analysis

- Commitment to action

These 6 items are often thought of as links in the “chain” of decision quality. And, when each item has been given its due, that will lead to a good decision.

Unfortunately, there may be traps you can fall into along the way to reaching a decision - leading to negative, costly, or dangerous outcomes. By examining two elements of decision quality — framing and alternatives — we’ll illustrate how to approach these correctly to avoid the potentially detrimental downfalls and achieve an optimal outcome.

Framing the Correct Problem

It’s absolutely necessary to frame the problem you’re facing. Without a deep and complete understanding of the problem, you can’t determine the best decision. When faced with a problem that demands a decision, many decision makers jump in with both feet when it’s actually better to pause, reflect on the situation, and ask:

- What is the problem here?

- What is our intention in solving it (purpose)?

- What is the scope (dimension) of this problem?

- What mental perspectives are you bringing to it?

Questions like these help you to frame the correct problem. And, in most cases, framing is the first element of the chain of decision quality. Frame the problem appropriately and you’ll be halfway to a good decision. Frame it incorrectly and you’ll be solving the wrong problem.

Developing Alternatives is Non-Negotiable

Constructing and proposing a rich set of alternatives can be a task too burdensome for most. It’s easier to settle, instead, for whatever comes up first. And that’s a shame because the optimal decision is only as good as its best alternative.

Anyone making a decision is obliged to select the alternative with the greatest value. Thus, the list of alternatives should be large and sufficiently varied to include a full range of possibilities. Strategic decision making should also include “good” alternatives. To be considered good, an alternative must be:

- Creative: Creative alternatives are not immediately obvious or in line with conventional thinking - they require thinking outside the box.

- Significantly different: Alternatives should be considerably different from one another in ways that truly matter.

- Representative of a broad range of choices: It’s important to “span the space” because you never know in advance where the greatest source of value may be hidden.

- Reasonable contenders: Some of the choices that people offer are nothing more than “decoys” intended to make another alternative look good by comparison.

- Compelling: Every alternative should represent enough potential value to generate interest and excitement.

- Feasible: A feasible alternative is one that can actually be implemented and that is under our control. If it isn’t feasible, it doesn’t belong on the alternatives list.

- Manageable in number: Three alternatives are generally better than two, and four are likely to be better than three - but 15 isn’t better than four. What you need is a manageable set of alternatives - one that covers the range of distinctly different choices while remaining within your ability to analyze and compare.

Decision makers who don’t consider alternatives move forward with a huge blind spot, leaving substantial value on the tab.

Be Strategic in Your Decision Making

When it comes to framing, you need to make sure you’re solving for the correct problem. In our Decision Quality course, taught in partnership with Strategic Decision Group, you'll be equipped with the tools and questions to ask when framing problems appropriately.

When looking at the alternatives, you need to have creative, viable, feasible options to present. This is just one of the many pieces of the Strategic Decision and Risk Management puzzle. The breadth and depth of decision quality can help decision makers feel confident in the process. All six of the decision quality elements form a chain of quality that allows no space for human biases, false assumptions, or organizational politics. The framework eliminates the short-sighted thinking that so often undermines decisions. By ensuring all of the links in the decision quality process are strong and bulletproof, you will be confident in the process and in your calculated and carefully determined decisions.